-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Nikhil D Gotmare*, Parul Jain, Ritu Arora, and Isha Gupta

Corresponding Author: Nikhil D Gotmare, Guru Nanak Eye Centre, Maharaja Ranjit Singh Marg, New Delhi, 110002, India

Received: February 25, 2021 ; Revised: April 4, 2021 ; Accepted: April 7, 2021

Citation: Gotmare ND, Jain P, Arora R & Gupta I. (2021) Consequences of Traditional Eye Medication Use in Developing Countries: A Perspective. J Clin Ophthalmol Optom Res, 1(1): 1-4.

Copyrights: ©2021 Gotmare ND, Jain P, Arora R & Gupta I. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Abstract

This review aims to highlight the potential consequences of the use of traditional eye medications (TEM). The use of TEM which are a form of biologically based therapies is still rampant in developing countries. Breast milk and plant products are amongst the most commonly used TEM. The use of TEM may lead to ocular surface damage and infections, leading to decreased visual acuity and even blindness. In this article we discuss the various TEM used, the potential damage they cause to the eye, and why people resort to TEM. The solutions to decrease the impact of TEM use in this subset of the population are also discussed.

Keywords: Traditional eye medicines (TME), Corneal Blindness, Corneal Ulcer, Keratitis, Primary eye care

INTRODUCTION

Traditional eye medicines (TEM) are a form of biologically based therapies or practices that are instilled or applied to the eye or administered orally to achieve a desired ocular therapeutic effect. TEM is crude or partially processed organic (plant and animal products) or inorganic (chemical substances) agents or remedies that are procured from either a traditional medicine practitioner (TMP; synonyms: traditional alternative medicine practitioner, traditional healer, spiritual healer) or non-traditional medicine practitioners that could be the patient, relative, or friend [1]. The use of TEM is apparently still rampant in developing countries, especially in rural areas.

Traditional Eye Medicines Used

In a population-based, cross-sectional study in the rural population of north India, TEM commonly used were in the form of ‘Surma/kajal’, honey, ghee, and rose water. Some peculiar TEMs being instilled in the eye by this population were alum water, milk, plant juices, saline water, breast milk, turmeric, jaggery, curd, garlic, goat’s milk, ‘neem’, powdered horn of deer, excreta of donkey, lemon juice, turpentine oil, coconut oil, warm tea leaves, ginger juice, onion juice, ash of hukkah, mustard oil, fenugreek, carom seeds (ajwain) and leaf extracts [2]. Similarly, a hospital-based study from Sao Paulo, Brazil also reported the use of homemade, traditional products like boric acid, normal saline, and herbal infusions for ophthalmic emergencies [3]. Breast milk (40%) and plant products (29%) were found to be the most commonly applied TEM in a study conducted by Chaudhary [1].

Such substances may be acidic or alkaline. No particular attention is paid to the mode of action (antibiotic/steroid), concentration, and sterility as most of these preparations (plant/animal extract mixture) are made without regard for hygiene including using contaminated water, saliva, local gin, and even urine [4].

Not only are traditional remedies easily available and used in India and the Middle East, but they are also used by the immigrant Asian population in the U.K. as a result of persisting cultural practices. Unfortunately, such remedies rarely go through stringent preclinical/clinical toxicity testing. The lack of quality control, false or misleading claims on labels, presence of toxic metals and other contaminants in traditional eye products is a cause of concern. Unsuspecting individuals unaware of this, consume such preparations in good faith believing that “traditional” or “herbal” equals “natural” and “nontoxic” i.e., safe [5].

Some plant products that are found to be used are: Extract of Kanthakari (Solanum xanthocarpum) root, Nagarmotha (Cyperus scariosus) or Sendha Namak (Rock Salt) or Mulethi (Glycyrrhiza glabra) or Pippali (Piper longum) that are prepared with milk are used for fomentation [6]. Paste of Mulethi (Glycyrrhiza glabra), Harida (Curcuma longa), Harad (Terminalia chebula), and Devdaru (Cedrus deodara), in equal parts are prepared with goat milk or water and are concentrated. An Anjan (Collerium) is prepared and applied. Steam distillates of plants like Punarnava (Boerhavia diffusa), Palash (Butea monosperma), and Mulethi (Glycyrrhiza glabra), are used as eye drops. Extract of Amla (Embica officinalis), Harad (Terminalia chebula) and Bahera (Terminalia belerica) are used for washing of eyes [6].

Prevalence

TEM is being widely used by the Indian population, Prevalence being higher as compared to a hospital-based study conducted in the Nigerian population [2]. Various studies in Nigeria and other parts of Africa also have reported that a large number of patients still use TEM before presentation to the hospital [7-11]. The use of TEM is not dependent on the participant’s age, gender, level of education, religion, or marital status [2]. Similar findings were reported from Sao Paulo in Brazil [3]. Instillation of TEM was reported to be higher in subjects residing in rural areas, females, the elderly age group, Muslims, illiterates, and people who sustained ocular trauma [1-2]. These observations were common in developing countries like African countries, India, Pakistan, and some other Asian countries.

Consequences of TEM Use

TEM may lead to the development of infection due to various factors such as contamination, acting as a carrier for infection, creating a favorable environment for the proliferation of pathogens, delay in the use of proper anti-microbial therapy. Due to their direct harmful and noxious effect, they may cause corneal epithelial breakdown and thus aid in bacterial penetration to deeper corneal layers causing an increased occurrence of infectious keratitis, corneal opacities, and staphylomas in the developing world including India. The use of TEM is recognized as an important contributory factor for development as well as for the delayed or complicated presentation of corneal ulcer cases, especially in rural populations [2,7], [11-14]. The development and exacerbation of corneal infections occurring due to these harmful practices, frequently result in poor visual outcome [7, 20, 21]. There are reports of bilateral corneal blindness after the use of traditional eye medicines in form of powders that are used to keep the patients “awake” after snakebite (according to the myths still rampant in rural areas) [5]. The chemical analysis of the flaky powder in a case report revealed it to be potassium nitrite.

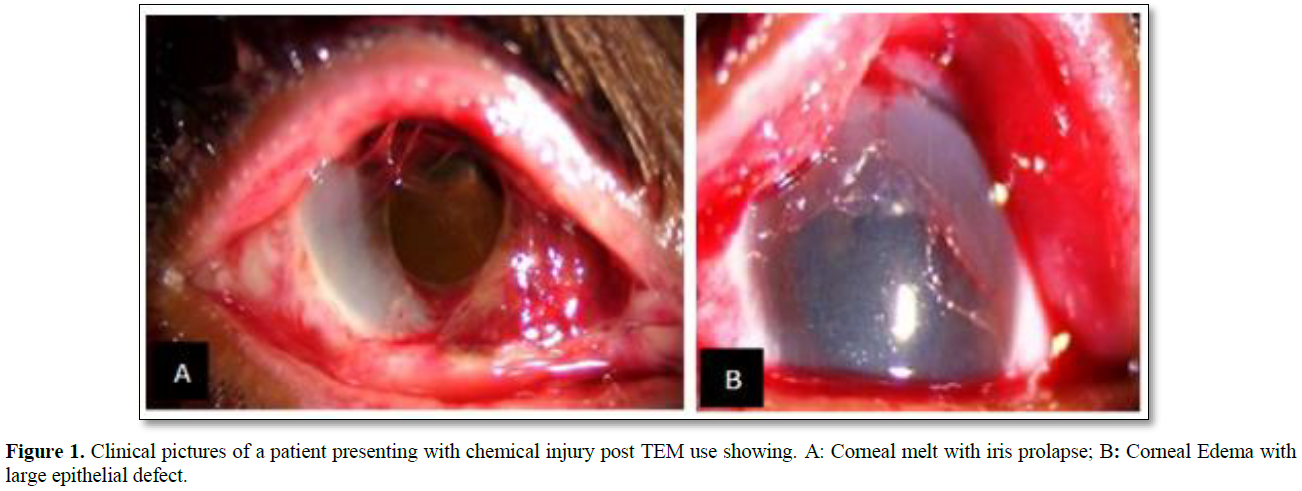

Instillation of potassium salts in the powder leads to severe ocular chemical burn in both eyes (Figure 1) [15, 16].

Prajna [14] reported that 47.7% of patients with corneal ulcers in South India [14] and Singh from Nepal reported that 57% of the patients with corneal ulcers used TEM [17]. While, Yorston and Forster [18] in Tanzania revealed that 25% of corneal ulcers in 103 patients were associated with the use of TEM. The use of harmful TEM has been reported in epidemics of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis in Africa [19].

A study conducted by Choudhary et al found that the most common symptom was poor vision for use of TEM. Visual acuity was found to be higher among non-TEM users and the difference was found to be significant [1]. Other side-effects of TEM include ocular burns, skin rashes, kerato-Conjunctivo-uveitis, purulent conjunctivitis and iridocyclitis etc. [4].

Why People Resort to TEM

The barriers for not utilizing ophthalmic services were found to be lack of access to hospitals and health care facilities, low rural education, objection raised by older family members, economic constraints, proximity and relatively easy access to TEM through local healers, relatives, friends, and neighbors. For some, the ophthalmic disease was not a priority and no treatment were sought despite ocular injury instead patients presented to non-ophthalmologists and traditional healers, ‘hakim’ (a physician using traditional remedies in India and Muslim countries), ‘vaid’ (a practitioner of the ayurvedic system of medicine) and other non-registered practitioners [2]. Similar barriers have been reported by various studies [22-24]. The perception of supernatural forces as the cause of blindness has also been documented as a barrier to the use of orthodox medications [7,25].

What can we do: There is a need to increase awareness amongst the medical fraternity and the public regarding the harmful effects of TEM.

Public Awareness and Education

People residing in villages and rural parts of the developing world, usually tend to consult local healers or elders of the community (who are the commonest sources of eye-related health information in the rural population) in the event of ocular disease as they believe that diseases are caused by violating traditional societal rules [11]. Hence, large-scale efforts at public education need to be evolved and implemented through ground-level health care volunteers and local community participation to resolve the health-related barriers, understand cultural habits and avoid harmful traditional practices.

Uncontaminated and lead-free eye cosmetics/medications that are safe to use should be marketed to prevent childhood lead poisoning and unnecessary exposure of lead to adults [5]. Caution needs to be taken in the use of ayurvedic and indigenous eye drops, which are available off-the-counter without consultation of an Ophthalmologist. Changes should also be made to the inadequate and misleading information found on the labels of such medications.

Healthcare

There is a need to improve accessibility, affordability, and availability of quality ophthalmic services for the general population [2].

Primary eye care workers have a very important role to play in the prevention of blindness from TEM as they are the first point of contact for ocular conditions. They must be trained to recognize minor ocular ailments and equipped for treating them. Their contact with the community is important in discouraging the use of TEM. Nurses and community health-care workers should be trained to recognize and promptly refer cases of corneal ulcers and trauma to ophthalmologists [1]. Early intervention in the form of medical or surgical therapy wherever indicated may help preserve the vision [15].

Research

There is an increased worldwide interest in the use of “herbal”/ “natural” medicines, thus positive steps towards the safety and not just the efficacy of such products should become a research priority. These products should undergo quality control testing and toxicity studies. Efforts should be made to increase the modern application of traditional knowledge for their scientific rationality and therapeutic application.

There is a need to study the overall prevalence of the use of TEM including its use amongst the urban population to provide a holistic picture of its use. It is imperative to conduct qualitative research studies to understand people’s behavior in different populations to combat the current problem. Reporting of cases arising as a consequence of TEM use would make the ophthalmologists and general medical practitioners aware of the possibilities.

CONCLUSION

The use of various organic and inorganic agents as TEM is still rampant in rural areas of developing countries. The use of TEM may lead to ocular surface damage and infections, leading to decreased visual acuity and blindness. There is a need to increase awareness and education amongst the public regarding such consequences and to overcome the barriers to not utilizing ophthalmic services by improving health care delivery. Research regarding safety, toxicity studies, and quality control should be conducted for TEM. Studying the prevalence and reporting the cases arising as a consequence of the use of TEM would increase awareness amongst health care providers.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

None

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

None

REFERENCES

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :